Ammunition Review: .300 AAC Blackout

By Nick Leghorn on July 29, 2011

There are problems with the 5.56x45mm NATO round, especially out of short barreled guns — mainly that its loud and underpowered compared to what the enemy is using. Many have tried over the years to fix this problem, coming up with wacky calibers like .300 Whisper, 6.8 Rem Special, 6.5mm Grendel, and more recently Wilson Combat’s 6.8mm offering. They all work, but they all have fatal flaws. AAC has come out with a new round that they claim works with existing AR magazines, bolts, bolt carriers, and fixes all the short distance and short barreled problems of the 5.56mm NATO round while still being as quiet as an MP5-SD. Naturally we asked them to put up or shut up, and they invited me out to their Atlanta, Georgia factory to do just that. The put up part, that is.

300 Blackout, which has turned out to be one of the biggest things going for this company, which we’re totally excited about, that was sort of an accident. Just like I value the relationships here, I have a personal relationship with everyone who works here, and with our customers on the military and government side it’s the same way. And those relationships lead to new products. They came to us about a new caliber and that’s where it started. The 300 whisper concept, we need to commercialize it and there are some things we need to fix with it…

[...]

[J.D. Jones] maintains a great relationship with a guy who runs one of the military groups that we deal with. Them working together came up with .300 Blackout. They had tried .300 Whisper, and J.D. Jones delivered this group a few samples that worked great. They delivered them 30, 7 of them worked. [Getting .300 BLK to work better] was one of [those] things – getting it SAAMI approved and standards, figuring out how to get the most velocity out of supersonic, making it accurate, making it feed reliably from 30 round mags…

We were working with Bill Wilson somewhat too, and he thought it was a great idea. Then [he] decided ‘oh, it’s not accurate, I’m going to do my own cartridge.’ And he’s doing… Ours is 7.62×35, he went with a longer case – 40. He only cares about supersonic, where our original requirement was it had to be subsonic as well. I was reading yesterday, like you buy these modified – it sort of gets away from the whole beauty of doing this for an AR-15 in my opinion. His you have to modify the magazines, and will only feed like 15

rounds in a 20 round mag or 20 in a 30 round mag…

These were our original requirements for this caliber: Muzzle energy has to equal or exceed the AK-47. .30 Caliber projectile. Use unmodified 30 round magazines to full capacity. Use unmodified AR-15/M-16/M-4 bolt. Gas impingement

system. Shoot super and subsonic. And one thing that was nice, but was not a ‘deal killer’, was non-adjustable gas system. Cycle all four ways – subsonic suppressed and unsuppressed, and supersonic suppressed and unsuppressed.

So let’s take these claims one by one.

First, does it actually work using standard AR-15 magazines, bolts, and the gas impingement system? Well, we saw it in action at NDIA doing just that.

Following that video, Kevin gave me the magazine we were using to keep. I have it right here in my hand as I write this, actually. Let me snap a quick picture…

In the foreground is the magazine being used in the .300 BLK gun in the video, and in the background is a magazine that Magpul sent me recently for the AR-15 magazine testing. The magazines are identical, something that can’t be said for most of the funky “5.56 replacement” rounds. But it gets better.

The reason all the standard AR-15 parts work when using a .300 BLK round is that AAC used 5.56 NATO as the “parent cartridge.” What that means is that you can manufacture brand new .300 BLK brass using spent 5.56 NATO brass simply by trimming off about a third of the case.

In the video above I walk through the steps to do exactly that — turn 5.56 brass into .300 BLK brass — and it takes less than 10 minutes to go over everything. The only additional tools you need are a set of .300 BLK dies. Right now ammunition is a tad expensive ($0.90/round to $1.09/round), and by reloading spent 5.56 into .300 BLK you save about 2/3 of that cost (it runs about $0.20 to $0.30 per round).

Here’s a nice picture showing the whole progression from spent 5.56 case to loaded .300 BLK (the last step is polishing, BTW). It’s actually not a hard process, but if you’re adverse to trimming your own brass then ready made .300 BLK brass can be purchased at a relatively reasonable price from a number of online vendors.

Speaking of ways to get ammo if actual .300 BLK ammo isn’t available, ammunition compatibility is another reason the .300 AAC Blackout round outperforms the competition. The .300 Whisper cartridge has been on the market for a while now and can be found in most gun stores around me, but .300 BLK is still relatively new and ammunition is scarce. Thanks to the higher chamber pressures and larger cartridge of the .300 BLK round the firearms are able to accept and safely fire most .300 Whisper ammunition. I did an Ask Foghorn article about that very question and it goes into some more detail, but .300 Whisper in a .300 BLK gun is generally cool while the opposite is dangerous and will result in malfunctions.

For the rest, we traveled down to AAC’s factory in Georgia for a live fire demonstration and to see how these puppies are put together. Check this out.

I watched John Hollister pull a random AR-15 bolt out of a 5.56 upper and use it in a .300 BLK upper when I shot with him, the bolts are identical. The gas impingement system is in fact present and functioning. From where I’m (very comfortably) sitting it looks like they met their basic design specs.

But what about everything else?

Two major claims remain, specifically that the gun is as quiet as an MP5-SD and that it’s more accurate. Let’s start with the sound suppression, as that was the more fun one to do.

This clip is in the full .300 BLK video, but I pulled it out as it completely answers this question. It’s only about a minute long. Take a peek.

Is it really as quiet as an MP5-SD? No. Myth busted. Nuh-huh.

But it’s damned close.

Standing in front of the guns the difference is pretty easy to spot. The .300 BLK gun “pops” just a touch more than the MP5-SD. Considering that the gun is basically firing an AK round I’d say that’s a damned fine accomplishment. So while it may not be “as quiet” as an MP5-SD, it’s close enough.

Here’s an interesting fact you can impress your friends with: the barrel of an MP5-SD is actually designed to vent off gas from the 9mm round and turn supersonic ammunition into subsonic ammunition. We were shooting standard, straight out of the box supersonic stuff all day with the 9mm ammo, which means the MP5-SD was actually getting far less muzzle energy than a Glock 19. So when you’re comparing the noise the two guns above are making, remember that the MP5-SD is pushing a 115gr projectile 935 feet per second, and the .300 BLK round is a 220gr behemoth zipping along at 1,010 feet per second. In USPSA speak, that’s a power factor of 109.25 for the MP5-SD and a whopping 222.2 for the .300 BLK. And yet they sound almost equally as quiet.

John also talked about something else. John, for those who don’t know, was in law enforcement for ages. He knows a thing or two about going into dangerous situations and needing to be stealthy. One of the things he kept bringing up was that an MP5-SD might be great for being quiet and maybe taking out a guard dog, a meth dealer who’s been up for three days and is so paranoid that he’s wearing full body armor probably isn’t going to go down to a 9mm round. Thanks to the gas impingement system, instead of suddenly being in need of that M4 that’s conveniently locked in your trunk all you need to do is swap magazines from subsonic to supersonic ammo and you’re able to dispatch Mr. Meth Head with ease. Try doing THAT with an MP5-SD.

In terms of accuracy, the reports are absolutely astounding.

With the 16 inch Model 7 light barrel, we did 10 groups of 5 rounds each with the 155 ammo and it was 0.8 MOA average. That is not a BS 3 shot group picked out of several. No discarded rounds. No flyers. No BS.

-Random guy on a gun forum

For reference, the accuracy of an MP5-SD is approximately 7-8 MoA. That’s “shooting a dog from 5 feet” accurate, not “oh shit that guy on the roof has an AK” accurate. I’ve done some unscientific testing for myself and even at distances most people would consider “long range” it’s a very accurate round.

I may or may not have been sitting in an office when Kevin read off an email confirming that accuracy with an AR and a 9 inch barrel. Not that I’d take his word without seeing the results, but considering the glowing praise this round is getting all over the internet I’m not discounting it either. Rest assured, a request has been placed for a .300 BLK upper to confirm some of this stuff. Along with a silencer. And a T-Shirt. And a trailer hitch. Moving on…

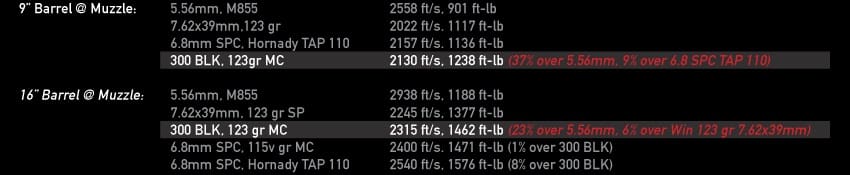

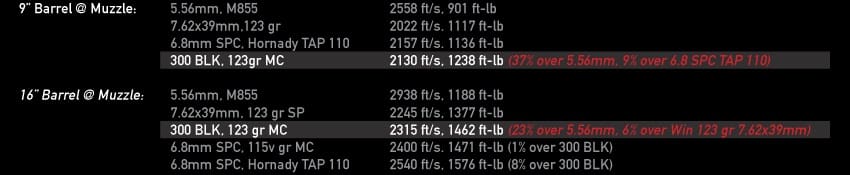

So what about the last part, about being as good if not better than an AK round, and fixing the issues with 5.56x45mm NATO? Luckily I’ve got a chart right here, its name is Paul Revere, and the chart says that if the weather’s clear…

Can do. Can do. The chart says the round can do. And if the chart says the round can do…

Speaking of penetration, there’s a video floating around claiming to show a SLAP .300 BLK round making Swiss Cheese out of a steel plate.

Again, I’m not saying I completely believe it until I see some better proof, but the sparks are pretty.

So what’s the final word? What’s my opinion on all this fancy .300 Blackout stuff? My personal opinion is that it’s frankly amazing. By simply changing out your barrel (and JUST the barrel) you get a completely different gun, one with more muzzle energy, able to just about sound like an MP5-SD, and 100% compatible with all of your existing gear. If you own an AR-15 (or even just a short action bolt gun) and you’ve been looking for something that’s easily suppressed, has great terminal ballistics, and is accurate as anything, this is what you want.

.300 AAC Blackout

Benefits

- More muzzle energy than 5.56 NATO

- Able to be suppressed more effectively than 5.56

- Uses a larger bullet for more damage to target

- Able to penetrate barriers more effectively

- Armor piercing and incendiary bullets available (if not completely legally)

- Supersonic and subsonic ammunition available

- Swapping between supersonic and subsonic requires no changes to the gun

- Can be made from 5.56 brass, easy to reload

Drawbacks

- Ammunition is not widely available

- Ammunition is currently slightly expensive

Overall Rating: * * * * *

I really can’t praise this stuff enough. This is like the chosen cartridge for those wanting to get just a little bit more muzzle energy and a little less noise out of their existing guns. If you’re just running an AR-15 for target shooting and 3-gun 5.56x45mm NATO is probably good enough, but if you’re hunting something, looking for a self defense / SHTF caliber, or needing something that’s quieter than 5.56x45mm NATO ever will be, this is what you need.

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Bookmarks